Educators everywhere know that COVID-19 has proved a crucible for higher education, especially a higher education system beset by rising costs, facing a demographic cliff, and struggling with the brave new world of generative AI. Many institutions, even before the easy access to AI apps and technology, have already been sent into oblivion. Those who have escaped (mostly) unscathed are able to do so because of massive endowments and unique, long-lived, and meaningful missions that speak clearly to their constituents. Those who are hanging on by a thread are doing so by pursuing paths that will prove deeply short-sighted, gutting to the very nature of higher education–witness the University of West Virginia.

But how has COVID changed enrollment patterns at a specific institution, and what can be done to capitalize on those trends responsibly? Enrollment can, in some measure, be a loose gauge of popularity or student choice; however, the nature of what is offered and who is teaching matters, too, as does faculty satisfaction with student success. And because student success is dependent on longer-term assessment of outcomes, we must be cautious about interpreting these data points in an over-simplified way.

So, for my second big project as a new Instructional Designer and Technologist at George Mason, I’ve been working with my mentor and colleague to tell the data story of online enrollment since 2015, specifically in the School of Business. Some questions we were interested in include:

- How has enrollment shifted by modality over the past 8 years?

- How have these shifts registered across different academic areas?

- What differences are visible between graduate and undergraduate programs?

- Why are these differences, and what do they tell us about the interests of these different student demographics?

- Which online courses have undergone the most sponsored development, and over what period of time?

- What online courses have not been regularly revised (beyond annual faculty updating), suggesting a place for support?

- Are there gaps in online offerings that may impact specific concentrations?

- Are there opportunities to serve student needs that haven’t yet been acknowledged?

- What other questions cannot yet be answered by this data?

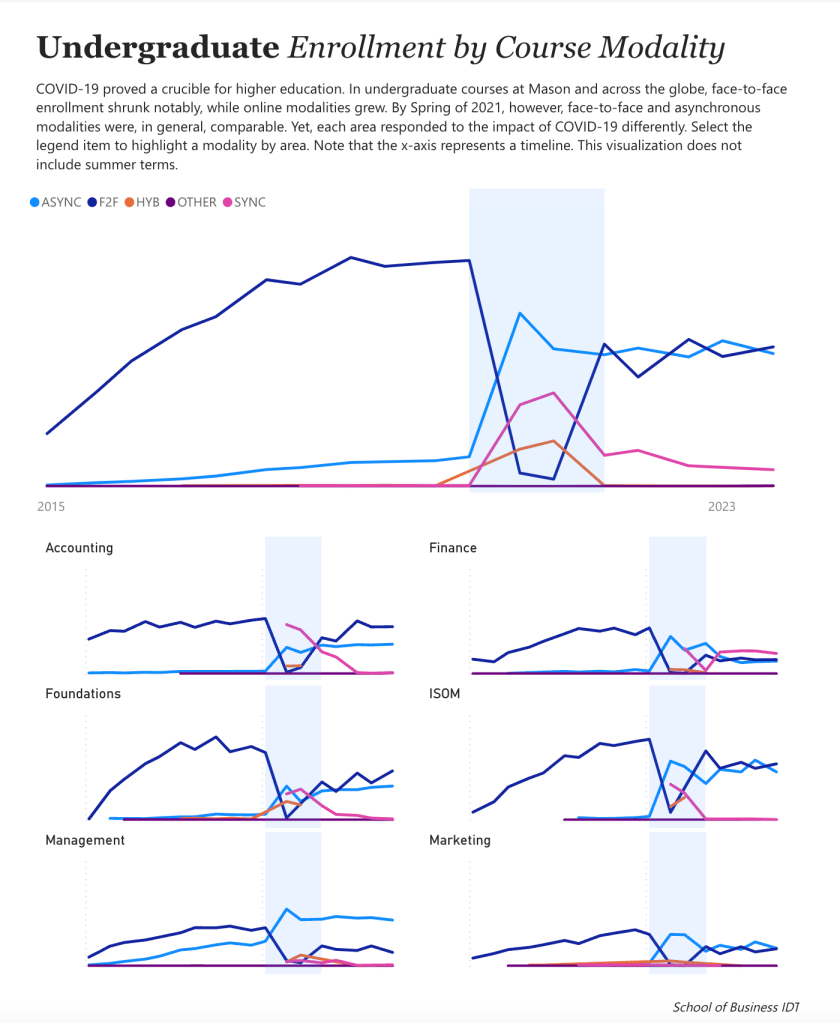

Our initial analysis has proven useful. One notable finding is that while COVID-19 has absolutely increased demand for (or perhaps supply of) online asynchronous courses, it has not done so monolithically across all academic areas.

For instance, face-to-face classes in Management have not returned to pre-COVID levels, while asynchronous courses have dramatically increased in enrollment. In Finance, all the modalities have become fairly well equalized, with a noted upsurge in synchronous courses–evident in no other academic areas. This would suggest that, given more research into companion data about faculty and student satisfaction, synchronous courses might be a better fit for Finance than many other areas.

Additionally, the impact of COVID-19 on undergraduate enrollment trends is very different in the graduate context.

Where the undergraduate context shows that face-to-face and asynchronous courses are becoming relatively equivalent in terms of enrollment after COVID, this is absolutely not the case in the graduate programs, which have notably different demographics–more mature, self-driven, working adults. In graduate programs, asynchronous and hybrid courses (hybrid is defined as students meeting in the same physical space as the instructor at least 50% of the time) are more popular than synchronous and face-to-face modalities. Indeed, before COVID, enrollment in face-to-face courses had been declining steadily since 2018, while enrollment in hybrid courses had been growing. Asynchronous course enrollment, which was on a slight upswing before COVID, is approximately equivalent to hybrid enrollment. Synchronous was also on an upswing before COVID, but–perhaps because it has similar demands on student time as face-to-face–that interest has waned notably post-COVID. Other modalities are preferred. (Keeping in mind of course that preference is not the same as taking what is offered, given that institutions everywhere seek full classes, whatever their modality.)

Overall, some programs are less disposed to continue asynchronous teaching, though in other areas, it is clear that students seem interested in–or at least are taking–more online offerings. Perhaps synchronous courses or hy-flex courses, currently less present, are a place for programs less focused on asynchronous course offerings to invest, especially given the similarities between face-to-face teaching and synchronous online teaching. Hybrid–and increasingly hy-flex teaching, which offers students both in person and online options simultaneously–may be more appropriate for such academic areas. Hybrid and hy-flex teaching, however, come with their own unique demands, which are especially onerous on faculty who must essentially prepare two very different experiences for their students.

It would be interesting to compare these trends to national averages or data from the DC-Metro area. I’ll talk about other data analysis in later posts, including how we’re visualizing sponsored online course development and the role of online courses in concentrations.

Have thoughts? Leave them below!