There’s been a lot of talk recently about the future of the college essay in the era of AI like ChatGPT and Jasper. Using artificial intelligence and the vast training material of the web, ChatGPT takes a user-generated prompt and returns an essay, a poem, or other genre of writing that is not only polished but also, to greater or lesser degrees, compelling.

ChatGPT takes a user-generated prompt and returns an essay, a poem, or other genre of writing that is not only polished but also, to greater or lesser degrees, compelling.

The release of ChatGPT this month prompted Stephen Marche to claim that “The College Essay is Dead”, and The Chronicle of Higher Education‘s Beth McMurtrie the subject with “AI and the Future of Undergraduate Writing.” Over a decade ago, Heather Horn–also of The Atlantic–wondered “Is the Essay Dead?”

But does the landscape look so dire if we consider that computers have almost always, since their inception, been involved in the teaching of writing?

In the 1980s, there was a long way to go; the most complex educational software in this vein was probably Story Machine, a specific instructional application of the historical concept of “story machines“, published by Spinnaker in 1982. It’s goal was to teach linguistic patterns and parts of speech using a Mad-Libs-type approach:

Fast-forward to 2022, and the rapid advance in AI for use in the development of content staring educators in the face, daring us to blink. Given the precarious position of the humanities already, and the English major in particular, which is focused on reading and writing, the rise of AI in “content creation” seems to add insult to injury. While the study of literature in colleges and universities has declined precipitously in the past 50 years, the study of writing seems to have largely remained strong, and the digital humanities is on the rise.

What should we be learning from AI that we’re not?

As a professor of literature and writing for almost two decades, and as someone who started her college career enrolled in computer science but who really wanted to be an artist, I think we should be learning not only that the landscape of literature and writing has been changing dramatically–but also that we need to embrace it.

Computers have been of interest in literary study since the advent of “humanities computing” in the late 1940s and 1950s. But it has been only in the past decade that institutions big and small are developing programs in digital humanities, and this has largely gone unnoticed in writing program curricula (for a lot of reasons including burnout and overwork). Writing programs are–and have been–turning to multimodal writing and multimodal literacy for the past decade, at least; but the reality of AI-generated content would seem to require that this shift be accelerated and radicalized.

Many of us have taken inspiration from folks like Ryan Cordell, whose concept of the Unessay has revitalized a lot of teaching in the humanities. I think this needs to become the rule of composition programs and literary study, rather than the exception. Developed in the 2010s, the unessay is a response to the formal essay assignment that has come to dominate higher education–the essay that Stephen Marche claims is dead. But if we remember Michel de Montaigne, who first used the term “essay” to describe his innovative, flexible approach to getting his multitudinous and shifting thoughts on paper (in the mid-1500s), we can see there is a clear precedent for experimentation in essay writing.

Essays that are crafted from video clips and voiceover; essays that take three-dimensional shape; essays as infographics; digital stories (digital research essays using Twine?); podcasts; there are many ways to think about analysis and writing. Performance is something that robots can do, but not yet well–the act of presenting content in human-centered, immediate ways can also be emphasized, and we can consider the elements of performance (costuming, delivery, storytelling structure, sets and props) as part of what it means to write in new ways. This should be exciting for us; but precarity has a way of discouraging experimentation.

As the nature of literacy changes, as the kinds of information we have access to changes, and as the medium that is our message changes, we need to respond in kind.

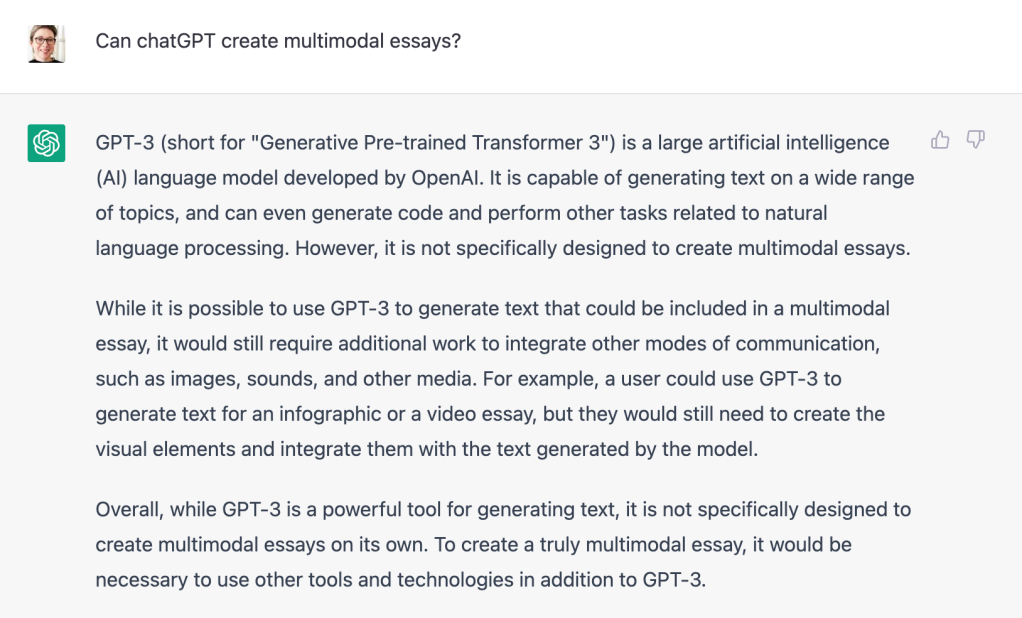

As the nature of literacy changes, as the kinds of information we have access to changes, and as the medium that is our message changes, we need to respond in kind. So perhaps we can take a page from this ChatGPT essay on the multimodal essay:

One Reply to “”